What happened to former child star Lora Lee Michel?

When Leslie Hannah and her sister were children, their aunt, Lora Lee Michel, appeared to them as a spectral figure, becoming real only when she appeared on screen.

A child actress in the 1940s, Lora Lee at 7 was billed as a “sensation” with “the greatest appeal since Shirley Temple.” She appeared in more than a dozen films, sharing the screen with Humphrey Bogart, Glenn Ford and Olivia de Havilland.

“We’d be watching TV and there’d be these films Lora Lee was in and my mom would turn them on and show us,” Hannah said. “That’s her. You can hear her voice!”

But Lora Lee was a shooting star — one that would quickly crash-land.

At 9, during the height of her celebrity, she stood at the center of a scandalous custody trial that grabbed headlines and captured the country’s imagination. It set in motion a chain of events that not only cut short her promising career but led to the unraveling of her life.

Just before her 10th birthday, a judge ordered Lora Lee to leave Hollywood and return home to Texas.

At 22, she landed in a federal prison.

Then she vanished.

Lora Lee Michel in Schulenburg, Texas, just before she moved to Hollywood and not long after she was adopted.

(Dania Maxwell / Los Angeles Times; Wright family)

The Schulenburg Historical Museum’s exhibit dedicated to Lora Lee.

(Dania Maxwell / Los Angeles Times)

“I have been looking for Lora Lee for a period of about 55 years,” lamented Barbara Wright Isaacs, her only surviving sibling. “I thought to myself, she’s either got to be dead or she doesn’t want to be found.”

Long before there was Britney Spears, Gary Coleman or Lindsay Lohan, there was Lora Lee Michel. A small-town girl with big Hollywood dreams caught up in the vortex of show business before many protections were in place for child entertainers. Hers was a classic tale of childhood stardom: the adorable moppet who got her once upon a time but not the happily ever after. Her story, as I soon discovered, was a parable, revealing the underbelly of Hollywood’s Golden Age and the perils facing child actors. But it was also one family’s search for answers and the buried secrets that have a way of eventually surfacing.

All families have their stories. But for Wright Isaacs and her two daughters, theirs was a ghost story.

“I don’t think there’s a time I didn’t know about Lora Lee,” Wright Isaacs’ youngest daughter, Allison Wallace, 50, told me. “My mom talked about her our whole life. I remember my mom crying, saying how much she wanted to find her sister and showing us the pictures of her when we were little kids.”

Last September, I traveled to Bandera, Texas, to the home of Hannah, 54, Wright Isaacs’ eldest daughter.

We sat in a room filled with Lora Lee’s movie memorabilia. Hannah pulled out a large three-ring binder stuffed with yellowed newspaper clippings going back 75 years, as well as correspondence and photographs. There, under framed movie posters, Hannah and Wallace unspooled the tale of their once-famous aunt and the family’s unsuccessful efforts to find her.

As they grew up, they began to understand the mythology around her. Wright Isaacs and Lora Lee were sisters, born into the same family but later adopted out to a pair of brothers. Yet they were separated for most of their lives.

For years, the family’s search yielded some clues, a few leads — but mostly dead-ends. “I don’t think there was ever a time they weren’t trying to find her,” Wallace said.

Hollywood is notorious for erasing people. But Wright Isaacs and her daughters refused to forget Lora Lee.

Lora Lee in an airport on her way back to Texas and a “normal childhood.”

(Dania Maxwell / Los Angeles Times; Associated Press)

They knew the broad contours of her life: the movies, brief marriages and the arrest for car theft that sent her to prison. But little else.

What they did know of Lora Lee was by turns anguished and dramatic. “I think everybody in her life just wanted to get whatever they could out of her,” Wallace said.

Wright Isaacs’ memories of her sister were bittersweet and fragmented. She still had the baby doll her sister gave her in 1950. The publicity photo signed, “Greetings from Hollywood to Barbara from Lora Lee,” sits in a frame.

In recent years, Wright Isaacs, 78, simply wanted closure; Lora Lee would be 81.

“I would like to not worry about where [she] is or what happened to her or why she never tried to find me,” she said. “I would very much like to know if she’s gone. If she’s deceased. Then maybe I can find myself resting in peace about her.”

I picked up the binder.

Though much of Lora Lee’s early years were well documented, once she left Hollywood there were major gaps in her life story.

Soon, I was watching Lora Lee’s films, excavating archives, sifting through old movie magazines, reading newspaper clippings, obituaries, county clerk records, letters and court filings. Like an anthropologist, I began tracing genealogy reports and tracking down anyone who crossed paths with her, trying to understand what they might tell me about who Lora Lee Michel was and what happened to her. Eventually, I discovered the many hidden threads of her life.

I started at the beginning in Schulenburg, west of Houston, in the heart of Texas Hill Country.

Tucked inside the Schulenburg Historical Museum, in the old Wolters Mercantile, stands a small exhibition devoted to Lora Lee. Photos and newspaper clippings chronicling her once-dazzling career are displayed among items stretching back to the town’s founding by German immigrants 150 years ago: a horse-drawn buggy, farm equipment, period clothing and 178 examples of barbed wire.

A drowsy railroad hub, Schulenburg was where farmers and ranchers once came to ship their cotton and hides. Today, people still refer to Schulenburg as “halfway to everywhere, middle of nowhere.”

Lora Lee remains its most famous resident and its most enduring mystery.

Lora Lee’s childhood home with her adoptive parents in Schulenburg, Texas.

(Dania Maxwell / Los Angeles Times)

Lora Lee Michel began life as Virginia Joy in 1940. She was born to Lena and Willie Walker Willeford in La Grange, a small town in Texas’ German belt, nestled along the Colorado River. She was one of five, possibly six, children the couple had together.

Money was tight. Willie, known as “Red,” worked as a truck driver, with a side hustle in the local cotton business. He frequently drank, and Lena frequently bolted.

“She was a runner,” Linda Robbins, one of her granddaughters, told me. “If she got too comfortable, she had to leave.”

Their union inevitably collapsed.

When Virginia Joy was 5, Otto Michel, a cotton broker, and his wife, Lorraine, adopted and renamed her Lora Lee. The childless couple lived in Schulenburg. At 57 and 56, they were old enough to be her grandparents.

The story of Lora Lee’s adoption, however, was told several ways.

In one version, Lena Willeford took off (some say with a Baptist minister) and left all of their children with Red, who was unable to care for them. He sent the older ones to stay with friends for a period, but had the younger ones adopted. In another version, the local children’s services came in and removed the entire Willeford brood, placing them with new families.

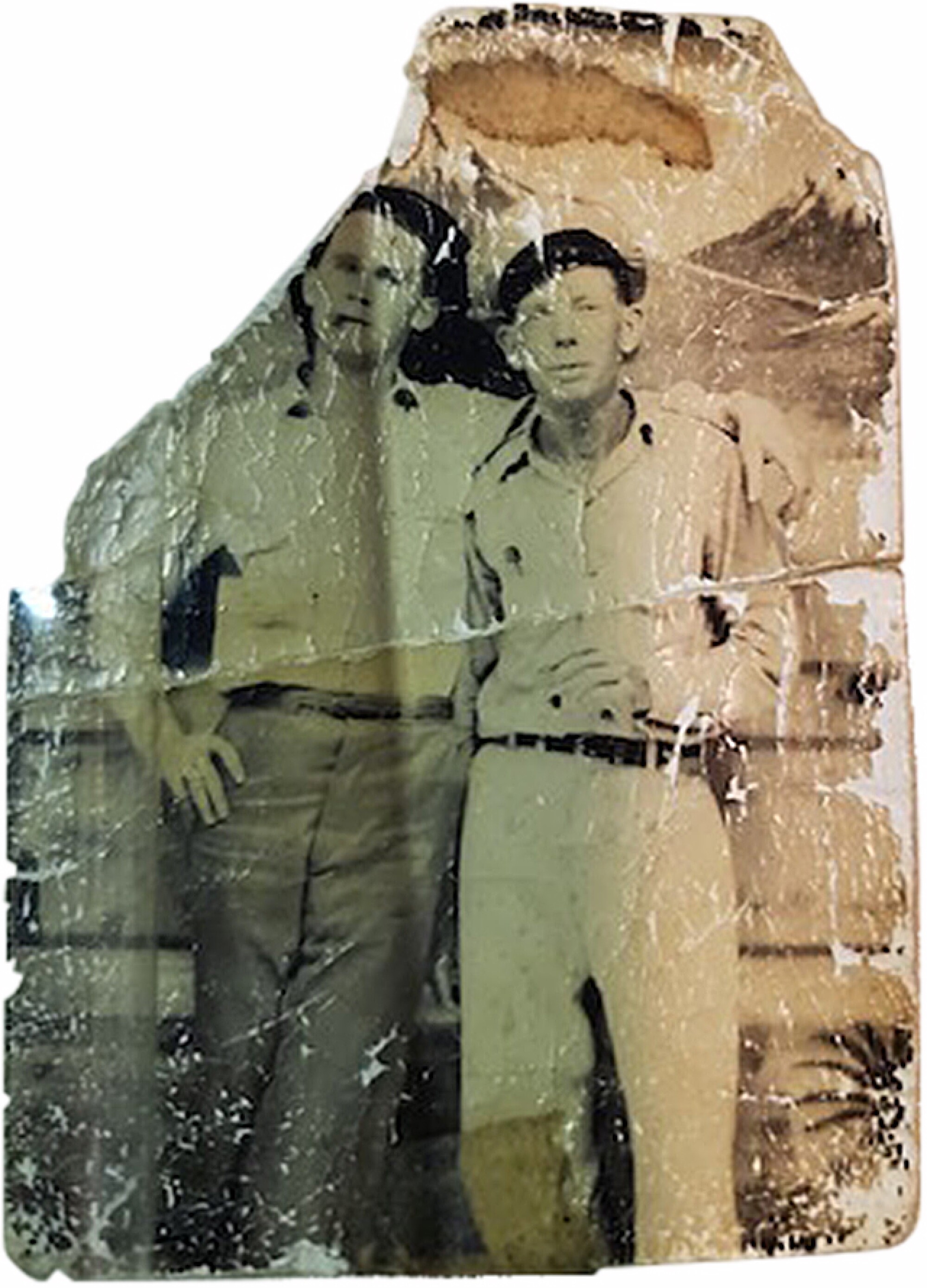

Willie Walker Willeford, right, Lora Lee’s biological father, in an undated photo.

(Linda Robbins)

The account that Lora Lee’s adoptive mother, Lorraine Michel, gave to the press was that she first noticed Lora Lee in a Schulenburg store. The two struck up a conversation and she learned of the family’s difficulties. The childless Michels had raised a great-nephew from the time he was 6, but he was serving with the U.S. Army Signal Corps in Japan. “We were lonesome, and when I saw Lora in the store that day I fell in love with her,” she told the New York Daily News in 1950.

“She was a ragged little waif. We took her in and gave her a home, and she loved us like she was our own child. We loved her too,” Otto Michel was quoted in one press account.

Otto’s brother Henry Michel and his wife, Lillie, who lived in San Antonio, took in Lora Lee’s younger sisters, Barbara Ann and Penny. They eventually adopted Barbara and sent Penny to a friend, who adopted her.

The home Barbara found herself in was perfectly ordinary and strict. But with Otto and Lorraine, Lora Lee found herself catapulted into a world where childhood make-believe came to equal money.

Lora Lee was a bright and charismatic child, with warm brown eyes and a smile that could light up a room. Lorraine taught the girl how to recite nursery rhymes, she said, and Lora Lee did so with a “sparkling charm.”

Soon, Lora Lee was lighting up the stage in local pageants.

While performing at a Lions Club banquet in Schulenburg, she caught the attention of a clutch of Texas dignitaries including Beauford Jester, then the Texas Railroad commissioner — soon to be the state’s governor. One bigwig was so impressed that he sent a telegram to Warner Bros. bosses saying, “If you don’t take a look at this child, you’re missing $1 million worth of Texas talent,” the family told me.

First discovered at a Lions Club banquet in Schulenburg in 1945, Lora Lee performed in plays, skits and pageants in her hometown.

(Schulenburg Historical Museum)

Lora Lee performing a skit at a Schulenburg Chamber of Commerce dinner in 1951.

(Schulenburg Historical Museum)

In 1946, the year after she was adopted, Lora Lee and Lorraine arrived in Hollywood. They moved to Crescent Heights Boulevard into a striking French Normandy-style apartment building that later housed Marilyn Monroe and Rock Hudson.

Otto remained back home to pay the “mounting bills,” according to a local news report.

Lorraine encouraged Lora Lee’s talents, enrolling her in dance classes and hiring a drama coach, fellow Texan Ona Wargin, who specialized in children.

Before long, Lora Lee began acting in TV and radio dramatizations and plays. Within a couple of years, she appeared in “I Remember Mama” at the El Capitan Theatre and in Clare Boothe Luce’s “The Women” at the Key Theater.

Invited to sing and dance at the Hollywood Roosevelt Hotel in front of 500 studio officials, Lora Lee ended the routine by sitting “on every lap in the place,” her mother boasted to their hometown paper in 1948.

Lora Lee in the 1948 film “Good Sam,” with fellow child actor Bobby Dolan Jr.

Lora Lee could deliver both charm and two to three minutes of uninterrupted dialogue. She landed her first big movie role, playing Lulu, the daughter of Gary Cooper and Ann Sheridan, in the 1948 romantic comedy “Good Sam.” She vaulted over all 10 girls up for the part, telling Leo McCarey, who’d previously directed the hit film “The Bells of St. Mary’s,” “make up your mind so the other nine can go home,” according to several press reports.

A succession of casting coups followed.

Lora Lee began appearing in the kind of pulpy, noirish films that now rotate regularly on the classic movie channels, such as “Mr. Soft Touch” with Glenn Ford. By 1950, she was earning $100 a day, according to The Times, equal to about $1,150 today.

A vivacious presence, her scenes with Humphrey Bogart in “Tokyo Joe” capture both her charm and ability to hold the screen with a Hollywood icon.

Child star Lora Lee Michel was a lively presence in her scenes with Hollywood icon Humphrey Bogart in the 1949 movie “Tokyo Joe.”

In 1949, she played the plucky young version of Jill in “Mighty Joe Young,” the story of a girl who lives on an African ranch with her father and raises an orphaned baby gorilla, which she later brings to Hollywood.

“She was breathtaking. She was fascinating. And every time I see the movie, I can’t wait to see her,” recalled Terry Moore, who played the grown-up Jill in the film, in a video interview with Leslie Hannah.

Moore, now 93, who was nominated for an Oscar for the 1952 film “Come Back, Little Sheba,” added: “I’ve been with all the child actors, and I’ll tell you, Lora Lee was the prettiest child actress I’ve ever seen in my life. She had what’s called star power.”

Schulenburg swelled with pride.

The town’s only cinema, the Cozy Theatre, usually played a single film twice a week, but made an exception for Lora Lee’s movies, giving them seven performance runs.

Lora Lee in a scene with Humphrey Bogart and Florence Marly in the 1949 film “Tokyo Joe.”

(Wright family)

Lora Lee played Gary Cooper’s daughter in the 1948 movie “Good Sam.”

(Wright family)

When “Good Sam” opened, the local paper devoted a full-page article to the girl they called “a 7-year-old package of personality plus.” In the accompanying photo, it appears as if the entire town turned up, holding a banner that read, “Lora Lee Michel, Schulenburg’s Own Movie Star.”

At 80, Gus Breymann can still vividly recall the excitement. Generations of his family owned Schulenburg’s pharmacy. Breymann now lives in Michigan, but he remembers how he and others used to drive past the Michels’ house.

“I think that was part of the surprise, that someone from that small German community could actually go to Hollywood and become a star as quickly as she did,” he said.

It wasn’t long before Lora Lee began playing bigger parts in more ambitious films.

She appeared as the younger version of the emotionally fragile character portrayed by Olivia de Havilland in “The Snake Pit.” The 1948 film chronicled a woman’s stay in a state mental institution. Nominated for several Academy Awards, it is considered one of the first realistic treatments of mental illness on film.

Lora Lee in the 1948 movie “The Snake Pit,” with actress Natalie Schafer. Lora Lee played the younger version of Olivia de Havilland’s character in the psychological drama.

(Wright family)

That same year, Lora Lee received top billing alongside Richard Denning and Frances Rafferty in the murder mystery “Lady at Midnight.”

The film’s studio, Eagle-Lion, centered its publicity campaign around Lora Lee. “This youngster has a charm and talent to make her one of the screen’s outstanding child stars,” its promotional materials proclaimed.

Numerous movie magazines echoed the breathless treatment.

As one columnist from Screenland declared earlier: “If she’s handled properly, wouldn’t be surprised if she’d turn into another Shirley Temple.”

On the morning of Jan. 12, 1950, Lora Lee’s acting coach, Ona Wargin, arrived at the Michels’ apartment to take her to a modeling interview. Wargin asked to have the girl “dressed prettily,” as Lorraine later recounted.

“I told Lora Lee to be a good girl, kissed her goodbye and then Mrs. Wargin said, ‘Don’t worry if we’re late. We’ll be at Paramount studio.’ I said good luck, Ona.”

Wargin, however, did not take Lora Lee to the interview. She went to the authorities, alleging that she had seen bruises on the actress. Lora Lee told the officers she was afraid of her adoptive mother, who she said mistreated her, starving her to keep her small for roles. She pleaded “never [to] send her back to that woman.”

Within hours, Lora Lee was placed in the care of the Rev. Elford D. Sundstrom, pastor of the United Brethren Church in Burbank.

Lorraine was arrested, charged with child abuse and neglect. She was later released on $1,000 bail.

Four days later, Otto flew to Los Angeles.

“There’s either a mistake or a frame-up and I’m going out there to see,” he told a local Texas paper, saying he had never supported sending their daughter to Hollywood. Now he planned to “fight and keep my home together.”

The couple hired Oscar Cummins, an attorney with connections to Columbia Pictures, where Lora Lee had made several movies.

In a letter to his brother Henry, Otto called Cummins “our red hot lawyer” and expressed his belief that they would prevail. “I feel so confident that God is with us.”

In the same letter, Otto seemed to have changed his mind about Hollywood, excitedly describing his visit to the Columbia backlot in Burbank: “You would have thought we were the greatest celebrities out here. It was terrific.”

Then came a plot twist. Out of the picture for the last five years, Lora Lee’s biological mother, Lena Willeford (now Brunson, after remarrying), got on a bus in Nederland, Texas, and traveled to Los Angeles. She claimed the Michels’ adoption was obtained by “fraud, trickery and under duress,” and she wanted the child back.

The national press was gripped by the unfolding drama swirling around the adorable child star and the seemingly greedy adults out to exploit her growing fame. Lora Lee became the subject of a sensational custody trial pitting her “real” mother against her “foster” mother, as the papers declared. “Fight on for Child Movie Star,” blared the front page of the Beaumont Journal in Texas.

Initial coverage portrayed the Michels as profiting off their adopted daughter. “Don’t overfeed Lora while I’m gone,” Otto was quoted as having told his wife, the New York Daily News said. “We have to keep her slim. We’re broke, and she’s the only thing we have to support us.”

Otto countered that he had nearly gone bankrupt keeping his wife and daughter in Hollywood, telling one newspaper, “I have sold all of my war bonds and sold some of my property to keep them out there, where I didn’t want them to go in the first place.”

In a flood of letters to his brother Henry, Otto fumed, laying out his own theory.

“We are up against one of the slickest, slimiest, diabolical frame-ups you could possibly imagine,” he said. “Ona Wargin has been working and waiting for this opportunity for two years. She and her degenerate racketeering husband and a clique have cooked up … one of the slickest deals you could imagine. It’s colossal.”

According to Otto, the Wargins had plotted to gain custody of Lora Lee for their own enrichment. He believed that the Rev. Sundstrom, the police and others he called “rich dupes” were part of the plan.

Otto was convinced that the Wargins “lured” Lora Lee’s birth mother, Lena, whom he called “poor misguided dumb Mrs. Brunson,” to Los Angeles.

The Michels now faced litigation on two fronts: a custody hearing and Lorraine’s trial for abuse and mistreatment. They hired private detectives and investigators to aid their case. Otto continued to correspond with his brother, often asking for money.

The matter of Lora Lee’s custody was the first issue to go before the court. The hearing began on Jan. 23, 1950, before Judge Alfonso Aloysius Scott.

The hearing was held behind closed doors. Still, significant details hit the papers.

“This is proving to be a worldwide international case,” Otto wrote Henry. “You can not imagine the wide publicity.”

Lora Lee claimed that her adoptive mother beat her with a hairbrush if she gained a pound, news reports said. She told the judge that she was so hungry that she was forced to steal milk and cheese left on her neighbors’ doorsteps.

Her adoptive father, Otto, she testified, took her to bars and gave her peanuts while he drank. Lora Lee told the judge she didn’t want to stay with the Michels, telling him that she “wanted to go back to my mother [Lena] and live in a shack.”

The same press that crowned Lora Lee as the second coming of Shirley Temple was now describing her as a “problem child,” “troubled actress” and “poor, little rich girl.”

Lorraine swore to the judge that Lora Lee had an “uncontrollable appetite,” due to a thyroid condition, but denied she had kept her from eating to keep her small for movie roles.

Lena’s time on the stand was fraught. She called the adoption a “fraud,” insisting that Red, her ex-husband, had threatened her with harm if she didn’t sign papers giving the girl away. She had no idea where Lora Lee was living and had no money to look for her. It was only after she saw “Good Sam” that she realized her daughter was in Hollywood.

Lena’s credibility took a hit when the Michels’ lawyer introduced the adoption papers signed by Lena and a letter she wrote to the Michels expressing her gratitude for them adopting her daughter. He also presented the Texas welfare report stating that Lena had abandoned Lora Lee and her five other children in 1945.

On Feb. 8, 1950, the drama spilled outside the courtroom just as the parties arrived to hear Judge Scott’s decision.

When Lora Lee spotted her biological mother in the hallway, she ran into her arms crying. Lorraine then rushed toward Lora Lee and a tug of war broke out. Photos of the incident show the ladies in their proper hats, dresses and handbags going at it. “Battle With Fists,” headlined The Times. Bailiffs charged in to separate them.

Inside the courtroom, hearing that Judge Scott denied the petition to remove her from the Michels and return her to Lena, Lora Lee burst into tears. “I want my real mother,” she sobbed, according to multiple accounts.

“Honey, there are a lot of things you don’t understand now. Mrs. Michel is your real mother now. You mind her and you know what will happen if you don’t, don’t you?” Scott cautioned.

“Yes, I’ll get spanked,” she replied. Scott then playfully turned her over his knee, gave her a slight pat and said, “Yes, like that only harder,” the Associated Press reported.

As a phalanx of flashbulbs popped, Lora Lee’s attitude quickly shifted. She posed for pictures, hugging and kissing the Michels. “My sweet mother! My wonderful father!” she cooed. She even jumped on the judge’s lap and gave him a kiss.

In 1950, trials involving the custody and purported abuse of Lora Lee captured headlines around the world. It was front-page news in the Los Angeles Times.

(Illustration by Jim Cooke / Los Angeles Times; Times Archive)

Scott instructed the Michels to take Lora Lee out of the movies and back to Texas for schooling as a “normal child.”

“There will be no more acting. Our baby is going to lead a normal, happy childhood,” Otto told reporters.

For her part, Lena slipped outside the courthouse quietly. She never saw Lora Lee again. (Lena died in 2000 in Jacksonville, Texas. She was 86.)

Three weeks later, Lora Lee made headlines once more when she began work on “Between Midnight and Dawn,” a criminal noir film involving cops, gangsters and a love triangle.

“The ‘retirement’ of Lora Lee Michel, 9, the little screen actress who was recently the subject of a stormy custody battle, didn’t last a month,” The Times splashed on its front page.

Lorraine explained, “Lora Lee is happy here. She loves acting and she loves Hollywood. It would be a shame to cut her career short at this point,” The Times reported.

Cummins, the family’s lawyer, described the return to acting as a kind of therapy to “eliminate the gruesome details of the custody trial from her mind.”

Barely a month later, on the evening of March 13, as the family awaited Lorraine’s upcoming abuse trial in Beverly Hills, Lora Lee ran away from home.

Newspapers gave this account:

At 9:30 p.m., an hour after Lorraine watched her daughter say her prayers and put her to bed, she noticed their apartment front door was open. When she looked in on Lora Lee, she was gone. Lorraine called the police.

In just her bare feet and wearing flannel pajamas, Lora Lee hailed a taxi. She gave the driver the Rev. Sundstrom’s address. As they headed to Burbank, Lora Lee complained that she was hungry and ordered the cabbie to buy her a cheese sandwich, milk and a slice of pie at a local drive-through.

At the pastor’s house, she said that she’d lost 10 pounds in the last month. “I had to get away,” he said she told him. “I couldn’t stand it any longer.”

Sundstrom called the Hollywood sheriff’s office. Lora Lee was taken into custody and sent to juvenile hall for the night.

“I can play with other children and get all the extra milk I want there. I don’t ever want to go back to the Michels,” she told authorities, adding: “I don’t want to be in any more movies. They’re too strenuous. In my last picture I had to do a lot of yelling. It made me very tired.”

The next day, the front page of the San Antonio Express asked: “What to do with a little girl who says she would rather eat pie than be in the movies — that’s the problem that confronted perplexed juvenile authorities yesterday.”

For Otto, the episode provided more evidence, as he had earlier written to his brother, that he was up against “a lowdown dirty plot” to gain control of Lora Lee. Ona Wargin had visited the girl at the pastor’s house against Judge Scott’s instructions. Otto was convinced that the drama coach was behind what was shaping up in his mind as a nasty conspiracy.

In the morning, Scott and an investigator from the district attorney’s juvenile office went to see Lora Lee. “One thing is certain,” he vowed. “We’re going to get to the bottom of this and I mean the real bottom.”

But first he needed to sift through the pile of discrepancies and contradictions. Lora Lee was examined and it was determined she had gained four pounds; she hadn’t lost 10 pounds, as she claimed.

Furthermore, the judge doubted her account of abuse. “I don’t believe her story. What she says are bruises look more to me as if she had run into a rose bush.”

During their meeting, Lora Lee pouted and acted “as if she were in front of the camera,” Scott said. “I was stern with her. And told her I wanted the truth. I said, ‘Don’t you put on any airs with me.’”

Before he left, Lora Lee told the judge she didn’t know why she ran away. She also retracted her story, telling Scott that she was never beaten or starved.

“She’s a precocious, emotional child who could get a lot of people in trouble,” The Times quoted the judge as saying. “I can’t tell when she’s acting and when she’s telling the truth.”

Scott made Lora Lee a ward of the court, ordered a psychological evaluation and placed her in the Boys and Girls Aid Society, a children’s home in Altadena. The Michels were given visitation privileges.

“Lora Lee has missed many beautiful things that should be a part of childhood. I intend to see that she gets them,” Scott said, declaring, “She definitely will not act in another picture while under my jurisdiction.”

Lorraine later told reporters she was baffled by her daughter’s behavior: “Sometimes I can’t understand Lora Lee. She’s so intelligent, but at the same time she’s only 9 years old. I think perhaps we should take her to a good psychologist.”

Parsing through the whiplash account of the hearing and its aftermath, it’s not hard to see that this child actor was acting out. Precocious and savvy but still a young girl, Lora Lee barely had the chance to discover, let alone develop, her own persona beyond her movie roles. She was separated from her siblings at age 5 and given a new name. Now she found herself toggling between the whims and agendas of the adults around her. And she was lonely.

Though Otto may not have been an initial booster of Lora Lee’s movie career, he and his wife quickly got caught up in the thrill of Hollywood, the attention the case brought and of course the money she made. He wasn’t likely wrong in his assessment of the Wargins and their cohorts, but he too appeared to be working an angle. After all, as one Texas paper calculated, Lora Lee’s films had earned her $14,000 (about $156,000 in today’s dollars).

On March 21, Lorraine’s trial for abuse and mistreatment of Lora Lee began in Beverly Hills Municipal Court, with a jury of eight women and four men.

Once again, the trial drew worldwide publicity.

At issue was whether Lorraine starved Lora Lee and beat her if she gained weight.

Held over four days, the snappy, rat-a-tat dialogue and theatrical turns gave the trial the cinematic feel of a black-and-white courtroom drama.

Lora Lee took the stand on the first day.

Wearing a patterned dress with a ruffled collar and ribbons in her hair, she wept and wrung her hands, describing how her adoptive mother whipped her with a hairbrush after she bought candy when she was supposed to be at Sunday school. “I couldn’t eat candy because I’d get fat,” she said. “The movies don’t like you to get fat.”

Lora Lee testified that she was constantly hungry, wandering the hallways of her apartment building “drinking milk left in the front door by deliverymen.”

But during cross-examination, Lora Lee abruptly changed her story. Her mother hadn’t whipped her after she stole candy, she said, but had put her to bed.

More shocking, Lora Lee claimed that her acting coach, Wargin, had instructed her on what to say. It was Wargin who told her to declare that she wanted to live in a shack with her birth mother and that her adoptive father took her to bars during the custody hearing. And it was Wargin who directed her to take milk and cottage cheese and not ask any questions.

When Lora Lee stepped down from the stand, she passed Lorraine, who gave her a hankie to dry her eyes.

A parade of witnesses provided testimony on the allegations and the idea that Lorraine had been set up — with Lora Lee caught in the middle.

When Lorraine took the stand, she described becoming anxious in December when Lora Lee hadn’t come home from school. “I found her wandering near Sunset Boulevard. She said she had gone to get some candy.” Lorraine asked her where she got the money. Lora Lee “hemmed and hawed, so I grabbed her by the arm. She said, ‘I took it from my teacher.’ I spanked her with my bare hand.”

Wargin fervently denied ever coaching the girl or instructing her to steal from her neighbors. She testified to seeing “marks on her arms — they were black and blue — her little buttocks were black and blue.”

Wargin claimed that Lorraine had admitted to whipping Lora Lee, leaving marks on her, and had asked whether she could leave her clothes on so they wouldn’t show during modeling. Wargin testified that Lorraine said of Lora Lee: “That little hussy has stolen more food and gained a pound and I’m determined to conquer her gluttonous appetite.”

In closing, Cummins declared that Lora Lee was the victim of a “debased conspiracy” to take her from the Michels. The case, he concluded, was “the most flagrant, rotten thing I have ever seen.”

After deliberating for seven hours, the jury acquitted Lorraine.

“We all pretty much agreed there wasn’t much to back up the beating charge,” one juror told the media, “but we were a long time deciding about Lora Lee’s diet.”

Afterward, Otto told reporters that he had put his trust in God, and “we know now he was on our side.”

Lorraine pondered taking a family trip to Europe. She described her most recent visit with Lora Lee, during which her daughter asked, “‘Mother when do I go back to the movies?’ But of course we’ll never put her back in pictures.”

In July 1950, the Michels returned to Schulenburg. Lora Lee, who remained in the children’s home in Altadena during the trial and after, joined them six weeks later. Judge Scott, who retained jurisdiction over the girl, authorized her return to Texas, where local authorities would have oversight.

The Michel case appeared to have greatly affected Scott. In subsequent years, he took an active interest in ensuring the contract rights of child entertainers. He also became a fierce protector of young, apprentice jockeys, implementing trust funds for them and rules for their treatment.

“I know he loved working with the young people, trying to help them,” the judge’s only surviving child, the Rev. Al Scott, 88, told me. He believed “there’s a pearl hidden in each person, like the oyster shells, and it takes time and effort and love to try to bring that out.”

On the evening of Aug. 29, 1950, Lora Lee, accompanied by the lawyer Cummins, touched down at the San Antonio Municipal Airport. Her adoptive parents, along with Lillie and Henry Michel and their adopted daughter Barbara, were there to greet her. Fearing that Lena Brunson might unexpectedly show up and cause trouble, detectives took up positions at the airport.

“It’s wonderful here. I love Texas. I hate California,” Lora Lee, wearing a party dress and ribboned pigtails, told the reporters waiting for her when she first landed. “Heck, I always got enough to eat,” she was heard to say.

A police escort took the reunited family to the luxury St. Anthony Hotel in downtown San Antonio. The city’s dignitaries gathered to meet them for a celebratory reception.

Several newspapers published a photo of Lora Lee and Barbara at the airport, hugging and smiling.

Barbara, who was 7 at the time, recalled the homecoming with her 9-year-old sister. It was the first time they’d seen each other since they’d been adopted, and Lora Lee “was very loving,” Barbara Wright Isaacs told me. At the airport, Lora Lee presented her with her own baby doll.

In their hotel room, Lora Lee entertained her sister, “telling me about all of her movie stuff and singing songs to me that she sang in the movies,” she said.

Wright Isaacs also remembered how Lora Lee went down to the lobby wearing an Uncle Sam costume. In front of everyone, she jumped atop the baroque, gilt-bronzed Steinway grand piano, originally built for the Russian Embassy in Paris, and belted out “Dear Hearts and Gentle People,” a popular song and an ode to a beloved hometown recorded by Bing Crosby a year earlier.

After Lora Lee’s return, however, Wright Isaacs recalled that her mother, Lillie, kept the girls apart. She didn’t understand why she was allowed to see her sister only under controlled, limited circumstances — or not at all. While all of Schulenburg had basked in Lora Lee’s movie glory, Wright Isaacs was never allowed to see any of her films. Once Lora Lee returned, Wright Isaacs said her mother referred to her sister as “that girl.”

According to Wright Isaacs, Lillie was not fond of her birth parents and she didn’t much care for the Michels either. Despite the public outpouring of affection in San Antonio, Lillie took every opportunity to keep them apart.

After the initial hoopla, Lora Lee’s return to a “normal” childhood in Schulenburg was anything but.

She was sent first to live in a convent, then to public school. Over the next two years, her every move was chronicled: playing with classmates, going to the movies and joining the Girl Scouts. “Lora Lee appeared chubby and in perfect health during her visit to San Antonio,” reported the San Antonio Express.

Lora Lee, back in Schulenburg after her movie career in Hollywood. Her activities were often chronicled in local papers.

(Wright family)

Lorraine had told reporters that they wanted “to give her a complete change from the bright lights and excitement of Hollywood.” And they did, exchanging the silver screen for local plays and recitals that Lora Lee now regularly performed in around Schulenburg and Houston.

“It’s easy to tell, when you see Lora Lee on the stage, that that’s where she was meant to be,” wrote I.E. Clark, a local teacher, reporter and playwright, in a newspaper review. “And you have the feeling it won’t be long before she’ll be doing it professionally again — and then for keeps.”

Despite their private assurances to Judge Scott and publicly in the media, the Michels continued to harbor movie star aspirations for their daughter.

Barely a month after she returned, the Michels were “tempted by the offers from the movies, radio and television that have been coming in,” according to a letter Clark wrote to an agent in New York. The agent, Annie Laurie Williams, had sold the movie rights to “Gone With the Wind,” and Clark proposed a book about Lora Lee. The Michels, he said, had authorized him to write her life story, with the goal of adapting it into a film in which the girl would star as herself.

By 1953, the picture had changed considerably. At 65, Otto died of pancreatic cancer. Lorraine followed two years later after a battle with lung cancer. She was 66.

Lora Lee didn’t attend either of her parents’ funerals, Wright Isaacs told me.

This is the point at which Lora Lee’s story began to fray and sputter. The Michels were no longer around to chase movie and TV roles. And Lora Lee, now a teenager, began to lead a more obscure life, its twists and turns seemingly lost to history.

But armed with the family’s recollections, I set out to find out what became of Lora Lee. I spent months hunting down information. I tracked dozens of individuals and made public records requests. Some were rejected. In other cases, I was told the documents I needed didn’t exist. Then in February, I received a trove of long-buried records held in a Federal Records Center in Fort Worth. They contained portions and summaries of Lora Lee’s psychological evaluations, school reports, criminal dockets, court and other filings. They made for some difficult reading.

Wright Isaacs had always heard that after Otto’s death, Lorraine took Lora Lee, then 13, to New York for an audition, and that Lora Lee had been arrested there for theft and ended up in reform school.

But the documents revealed that Lora Lee didn’t go to New York with Lorraine. She went to Houston. About the time Otto died, she was placed in the care of Catholic Charities there. Between 1953 and 1957, she cycled through four different foster homes.

A Catholic Charities report described Lora Lee as “emotionally unstable,” “very insecure” and with a “lack of a father figure during her early formative years.” The report noted that she had a “very abused childhood, never having a consistent home environment.”

Lora Lee briefly attended Mount Carmel Catholic High School, a Houston private school. She was a poor student who was largely truant. The Rev. Gerard Benson, the school’s principal, told investigators that he doubted Lora Lee had ever been in films, saying she was “mentally incapable.” But he pointed out that she was “always trying to act.”

Lora Lee dropped out after the 11th grade.

She got married the first time, at 17, to a man named Donald Mayo Ford on Feb. 28, 1958, according to court filings. A copy of their marriage license is dated Feb. 21. She was pregnant.

Lora Lee gave birth to a girl she named Donna Ann, who was put up for adoption with a Houston family.

According to the filings, Ford told authorities he had divorced Lora Lee sometime around November or December 1958. But I found no record of it.

I did, however, find something else: On Feb. 12, 1959, Lora Lee and Ford had another child, a son, William Henry. The boy was born with congenital atelectasis, a condition in which the lungs fail to expand normally at birth. He survived barely three hours, according to a copy of his death certificate.

Seven months later, Lora Lee checked herself into Austin State Hospital, a psychiatric facility, the oldest in Texas. “Please be assured that everything possible is being done for your niece’s comfort and welfare,” the hospital’s social service department wrote to Henry Michel, Otto’s brother. Wright Isaacs’ parents kept this from her, and she only found out about the hospitalization years later.

Wright Isaacs and her daughters didn’t know why Lora Lee was admitted. But an interview with her doctor later indicated that she had a nervous breakdown.

Lora Lee told her psychiatrist that she was raised by “foster parents” who were killed in a car accident. Her natural parents, she said, had also died in a car crash. This, of course, was not true. But the tale did have an echo: Her character in “The Snake Pit” not only shared her birth name, Virginia, but also had been admitted to a state mental hospital, and a car accident played a pivotal role in her character’s trauma.

She was discharged from the hospital after nine days.

In a letter to Henry Michel, the hospital’s superintendent noted that Lora Lee’s condition had improved. “It is our hope that the patient’s stay here will prove to be of value to the patient,” he wrote.

Soon after, Lora Lee returned to Houston, ricocheting around small office jobs. She sold magazines for a publishing company and worked as a clerk’s typist with the Houston Transit Co., earning $200 a month.

Mostly, however, she cycled through brief marriages and lots of trouble.

In February 1960, she met Joe Wendel Owen, a handsome former Marine nine years her senior. They wed on March 5, 1960, according to a copy of their marriage certificate filed in Fort Bend County, Texas.

Joe Wendel Owen, Lora Lee’s second husband, during his stint in the Marine Corps.

(Andi McWilliams and Kelly Smith)

Days after they married, Lora Lee wrote to her aunt and uncle saying that she planned to honeymoon in San Antonio for the weekend. “Joe would like very much to meet you. Since you are the only family that I have got,” she wrote. She added, “It’s been a long time since I have seen you, and I’m sure am anxious to see you all.”

The letter, typed on Houston Transit Co. stationery, was preserved in a plastic sleeve inside the binder that Leslie Hannah had organized. She told me her grandparents, Henry and Lillie, didn’t respond. Wright Isaacs believed it was the last time that Lora Lee attempted to contact the family.

I came across a puzzling detail. Owen died in 2013 at 81. But he had apparently married another woman five months after his wedding to Lora Lee, according to genealogical records. More bewildering, however, the Texas marriage register for Harris County notes this union as “unexecuted” in 1960. But another record indicated the couple married in 1985.

Owen had several siblings and two daughters. I was able to locate his surviving sisters and one sister-in-law.

When I reached his sister Frances Reid, she had no idea what I was talking about. “I don’t remember any Lora Lee,” she told me.

Mary Owen, his sister-in-law, said I must have the wrong person. “I think I’d know who his wife was,” she insisted.

I left a message with Patricia, his youngest sister. She didn’t respond.

I wondered whether I had the wrong Joe Wendel Owen.

In the meantime, I had emailed one of Owen’s daughters, Andi McWilliams. I told her that I was writing a story about “a former child actress who was married at one time to a man named Joe Wendel Owen, who I believe might be your father. Is that the case?”

Over the next four weeks, we went back and forth. She asked why I thought Lora Lee’s husband might be her father, but she didn’t yet agree to speak to me.

Then one morning McWilliams called me. “This is a humongous drama in our family,” she blurted out. “So that was my hesitation.”

McWilliams was warm, open and funny, not at all what I imagined given her terse emails. She explained that her father’s marriage to Lora Lee was a “deep, dark secret.” They were married for two weeks before Lora Lee left him. Owen met her mother shortly after and they planned to get married.

There was only one problem. He was still legally married to Lora Lee.

Owen needed to put an announcement in the newspaper. If Lora Lee didn’t respond, he could prove abandonment and legally sever the marriage. But McWilliams said her mother refused. “She didn’t want people to know that she actually was dating a married man.”

Owen only confided his relationship with Lora Lee to his youngest sister, Patricia.

McWilliams found out in 1992 when her parents split up. That’s when her father told her he had never divorced Lora Lee, meaning her parents hadn’t been legally married. Her mother refused to discuss the matter. “Everybody sees themselves as this is a good Christian family, and good Christian people don’t do this,” she told me.

Owen saw it differently. McWilliams said he was embarrassed that she left him. “He’s like, I can’t keep my woman, you know?” Still, when he confessed his hush-hush union, McWilliams said he spoke fondly of Lora Lee. “He said she just seemed to have so much light.”

McWilliams recalled how her father told her as a child that he had once dated “a Shirley Temple-like actress,” but thought it was just talk. He said she was in “Mighty Joe Young,” which McWilliams confused with “King Kong.” “I thought for years that Dad had dated Fay Wray,” she said, laughing.

Before we spoke, McWilliams tried talking with her mother. “My mom is still maintaining that this was all a secret — that she didn’t know that Daddy put one over on her,” she told me. But McWilliams was skeptical. Her mother had recoiled at the mention of Lora Lee, telling her daughter, “I cannot believe this woman has come back to haunt me.”

While scrolling through digitized old newspapers, I happened upon a line announcing the marriage between “Miss Lora Lee Michel and Mr. Carey Hand Bray” in the Fayette County Record, dated Sept. 6, 1960. They married a week earlier, six months after her marriage to Owen. It provided a new clue but also another unanswered question.

Lora Lee’s family had told me they knew she had married three times. According to press accounts, Lora Lee had stolen a car from an unnamed ex-husband who was a “druggist.” Hannah told me she had never heard of Bray. They assumed Owen was the druggist. But McWilliams told me her father was a Texaco regional manager before starting his own business.

When I looked into Bray, I discovered that he was a Houston pharmacist. He died in 2000 at 81. In February 1963, less than three years after he married Lora Lee, Bray married a woman named Billie June Whatley in Rosenberg, Texas. She died in 2016. They had eight children.

Before ruling this out as a curious coincidence, I tried calling Bray’s children, who were largely spread out across the South.

After mostly misses, one evening David Bray picked up the phone. I outlined my story and asked whether he had heard of Lora Lee Michel or any connection between her and his father back in 1960.

“I never heard of her,” he told me gruffly. “You are asking a 64-year-old man something that happened 61 years ago.”

Bray explained that Carey Bray had adopted him and his siblings when he married their mother. He didn’t understand why I had called him. He asked me whether I was a real reporter.

It was a shot in the dark. But before we hung up, I told him I had one last question. Perhaps he remembered hearing some crazy story growing up about a woman stealing his father’s car?

Bray went quiet.

“What’s her name again?” He told me he was going to make a call.

Minutes later my phone rang. It was Bray. “I just spoke to my sister Penny in Georgia,” he told me. “She knows everything. Call her.”

Penny Pearson was Bray’s eldest and only child from his first marriage. She needed little prompting. “Do you want the background of their little tete-a-tete love story?” she asked.

Pearson’s mother had died in December 1959 after a long illness. Lora Lee met Bray, 20 years her senior, at the Tangley Lounge in Houston. “My daddy was really lonely,” she told me. Pearson had gone to visit relatives in Florida, and when she returned her father introduced her to his new wife.

Lora Lee was striking, she recalled. “She had bleached blond hair and she was petite, very cute figure. She dressed very sharp.”

But Pearson took a dislike to her immediately. “Well, she was just really horrible. She said to me one time, ‘I screwed your father on the piano bench.’ I mean, and here I am, a 14-year-old girl!” She added, “But anyway, I think she was a con artist.”

Pearson told me that much of Lora Lee’s time with the Brays was spent pawning the family’s valuables including her mother’s fur coat, diamond ring, the china and even her own record collection.

Lora Lee spoke fleetingly of her Hollywood years. Pearson recalled her saying that “child actors kind of grow out of that cuteness” and that “she wasn’t getting any roles.”

They hadn’t been married very long before Lora Lee ran off. When she returned after a month, Bray took her back. “I made it my life’s mission at that point to get rid of her,” Pearson told me.

She didn’t need to worry because, soon enough, Lora Lee took off again.

But not before Bray bought her a new house in Westbury, a brand-new subdivision in Houston, and a new Ford Fairlane convertible. “It was black with a red rolled-in pleated leather interior,” said Pearson, and they “sported around in that.”

Just months later, she ran off again, this time driving off in the Ford, forcing Bray to take the bus to work. But, Pearson said, “I just had this feeling one day that she was going to come back by the house and take some more stuff out.”

She did just as Pearson predicted, driving up in the Ford one day without warning.

“If you want your car back, you better get home pretty quick,” Pearson told her father. “She’s here.” Pearson then sneaked out and let the air out of two tires. But when Lora Lee tried to get in the car, Pearson was scared she’d try and drive off, so she attempted to grab the keys. That’s when Lora Lee “bit me on the back and made me bleed.”

When Bray arrived and saw what happened, Pearson told me, “I hate to admit this, but my daddy socked her in the jaw.”

Looking back, Pearson laughed about the whole thing, telling me that her father remarried a “wonderful woman,” and she never heard from Lora Lee again.

Bray later told investigators the couple were married for about three or four months, saying they were divorced on Nov. 7, 1961, on the grounds of “incompatibility.” I wasn’t, however, able to locate a divorce record.

And while Lora Lee never bothered Pearson again, she didn’t leave Bray alone.

By February 1961, Lora Lee had moved to Corpus Christi. She was working as a waitress in a nightclub when she met Frank O’Neil Scott, a troubled former Marine sergeant who’d served in the Korean War. He was 12 years older, had a 10th-grade education and was a heavy drinker with a “long and serious history of writing bad checks,” court records show.

By the time Scott locked eyes with Lora Lee, he’d moved on from his first wife, Wanda Faye Headley, whom he met while stationed in Texas, and their four children, according to court records. Although Lora Lee and Scott were still legally married to previous spouses, they wed on July 22, 1961, in a “formal affair” at the First Methodist Church in Corpus Christi in what court filings called a “bigamous” marriage.

Then the pair embarked on a life of crime.

Some months after they married, the couple turned up in Scott’s Iowa hometown. They stayed in a motel where Scott “pimped” Lora Lee out, according to probation records. They were arrested after an informant and the sheriff ensnared them using a marked $20 bill. When he apprehended the couple, the sheriff found the money in the sole of Scott’s shoe.

They spent the week of Dec. 31, 1961, in jail. While there, the sheriff told investigators he “heard her tap dance.”

Bray, her previous husband, sent money to put her on a train back to Corpus Christi. The Scotts both paid $25 in fines for disturbing the peace and were “ushered out of town.”

In February 1962, Scott deserted the Army (he had enlisted after an honorable discharge from the Marines) and the pair began orbiting around Texas as well as in and out of the state, engaging in various schemes. Lora Lee’s probation officer indicated he believed that she started writing bad checks.

On June 21, while in Jonesboro, Ark., the couple looked at buying a 1957 Mercury. Instead of going for a test drive, the pair drove the car to Houston, according to court filings.

In Houston, Lora Lee reconnected with Bray. He agreed to give her use of his 1962 Ford convertible for the day. She and Scott took the car, embarking on a six-month journey traveling across seven states, running up $3,610 (about $34,000 in today’s dollars) on three of Bray’s credit cards they found in the glove compartment and a fourth one that Scott stole from someone else.

They lived in Missouri for three of those months.

There Lora Lee answered an ad for a governess put out by Leonard Voyles, a self-employed contractor. Voyles lived in Webster Groves, a suburb of St. Louis, and was divorcing his second wife; he had five children, according to her probation report.

Police described him as a “boisterous, unscrupulous, no-good individual, who has a violent temper and who cares for no one but himself.”

Lora Lee moved in with Voyles. He paid her $40 a week and room and board.

Around town, she called herself Mrs. Voyles and said Scott was her brother.

On Dec. 28, Texas Highway Patrol officers arrested Lora Lee and Scott driving Bray’s convertible near El Paso, according to press reports.

They were charged with two counts of unlawfully transporting a stolen motor vehicle across state lines and sent to Harris County Jail in Houston. They each faced up to five years in prison and a $5,000 fine.

For the first time in years, Lora Lee made national headlines. “Ex-actress Upstaged,” said one paper. In an interview carried nationally, she was asked what happened to her promising movie career. “I grew up,” she replied.

After spending almost two months in jail, on Feb. 8, 1963, Lora Lee was released on $1,000 bail. She returned to Webster Groves to live with Leonard Voyles.

Both Scott and Lora Lee pleaded guilty to one count of car theft. Lora Lee was sentenced to 13 months in prison. Scott received 27 months.

On March 9, 1963, Lora Lee was delivered to the Federal Reformatory for Women in Alderson, W.Va., court documents show.

Lora Lee’s probation officer noted that he found her “very impulsive,” concluding, “From every indication she has had a most unfortunate background.”

If she served out her full sentence, Lora Lee was to be released from Alderson in April 1964, court filings show.

My efforts to obtain her prison records were rejected.

I reached out to Denise Foster in Corpus Christi, one of Scott’s daughters with his previous wife, and left a message. Her husband, Larry, called me back. He said Scott was a sensitive subject for his wife. Scott, he told me, was a scoundrel and had numerous Social Security numbers.

But Larry Foster did say his wife had told him that she and one of her sisters had lived with their father and Lora Lee for a brief time. He didn’t know exactly when, but that his wife and sister-in-law called her “Loree,” and she helped them get their first training bras. He said they remembered her as being “really nice,” but not much else.

One of the strange turns in a story filled with strange turns was that for years Lora Lee’s birth siblings all lived within a 200-mile radius from one another in Texas. But most of them had no idea, even as they wondered what had become of one another. They were like scattered pieces of a jigsaw puzzle.

A few years ago, Leslie Hannah found Linda Robbins, the daughter of Bonnie Maner, one of Lora Lee’s older biological sisters. Bonnie died in 2001. By the time she found their youngest sibling, Penny Pellet, she too had passed away, in 2020.

“I have been looking for Lora Lee for a period of about 55 years,” Barbara Wright Isaacs, center, said of her sister. She and daughters Allison Wallace, left, and Leslie Hannah stand before movie memorabilia from Lora Lee’s career.

(Dania Maxwell / Los Angeles Times)

Robbins told me her mother, Bonnie, “always talked that she wanted to find her sisters.”

She remembered watching “Mighty Joe Young” on television and her mother piped up, “‘That’s my sister right there.’ And I was like, no, it ain’t. I said, ‘You’re lying.’ And she’s like, ‘No, that’s my sister. That’s Virginia,’” referring to Lora Lee’s birth name.

Robbins told me her mother thought Gary Cooper had adopted Lora Lee. “My mom didn’t really know everything, but she knew of her siblings, and she knew three of them were adopted out.”

Hannah, who had inherited the folder of Lora Lee memorabilia kept first by her grandfather, Henry Michel, and then by her parents, wrote a few letters and expanded her pursuit as new digital databases and social media emerged.

Hoping someone might respond, in 2010 the family posted on IMDb.com. They received a single reply from a man named Dennis Brown, who lived at the children’s home in Altadena with Lora Lee. He said he couldn’t help locate Lora Lee.

But he recalled, as an 8-year-old, spending time with Lora Lee. “Since we were all pretty much from broken homes, I guess we all felt varying degrees of loneliness,” he said.

As it turned out, Joe Wendel Owen, Lora Lee’s second husband, had been looking for her too.

During my first conversation with Owen’s daughter Andi McWilliams, she told me there was more to the story. When we spoke again, her sister Kelly Smith joined us. Their father kept “copious notes.” Smith had them.

They read me portions over the phone.

“Dad wrote that he had tried to find her,” Smith told me.

They had a whirlwind courtship and he didn’t really know much about her, he said. “She left with another man about a week or two after the marriage,” he wrote.

Owen later met and settled down with another woman, who would become their mother. But, the sisters realize now, their parents had not married because Owen believed he was still married to Lora Lee.

McWilliams told me her parents kept secrets and there was much she still didn’t understand. But it now made sense to her why, in 1985, instead of celebrating their anniversary, as they always had, they sneaked off to Fredericksburg, Texas, one weekend and remarried.

According to Owen’s notes, that same year he had sought help from a friend, Herb Fisher, to locate Lora Lee, presumably to legally divorce her. Fisher, who also knew her, came back and informed Owen that Lora Lee had died in 1979 of cancer, six years earlier.

Owen’s notes did not say how Fisher had learned that. But after living with this secret for 25 years, Owen was now free to legally marry McWilliams’ mother.

In March, I flew to Texas. Given the broad sweep of sorrows that I had unearthed, it seemed only right to discuss them with the family in person.

We gathered at Hannah’s house in Bandera. This time, Hannah’s husband, Phil, joined us along with her sister Wallace and their mother, Wright Isaacs.

We made small talk. Wright Isaacs showed me a few old photos of Lora Lee, remarking on what a beauty her sister was. In one, a smiling Lora Lee wears a hat; she was 5 or 6 years old at the time. It was just after the Michels adopted her, not long before she moved to Hollywood.

Once we settled around the dining room table, I began. “I wish I could be the bearer of better news,” I said, facing a ring of nervous smiles. “But, unfortunately, we believe that Lora Lee died in 1979 of cancer.”

The room went quiet.

The view across the street from Leslie Hannah’s window in Texas. Hannah took up the search for Lora Lee from her mother, Barbara Wright Isaacs.

(Dania Maxwell / Los Angeles Times)

Barbara Wright Isaacs said she finally got “closure” about her long-lost sister, Lora Lee.

(Dania Maxwell / Los Angeles Times)

Wright Isaacs was the first to puncture the silence.

“Well, this is sad news, but it’s closure for me. I don’t have to wonder anymore.” She reasoned that “God has a purpose,” before adding, “I knew in my heart she was not alive.”

I warned them that some of this would be tough going. I let the family sit with their thoughts. I asked whether they wanted me to stop. No, they said, they wanted to hear it all.

For nearly two hours I turned out my notebooks.

Each detail landed with a soft, painful thud. They were by turns stoic, contemplative, angry and sad. Lora Lee’s life unraveled in ways the family had never imagined. They were struck by the inventory of sadness that she carried — and the missed opportunities. This girl who was so bright and precocious became a woman lost in a maze of short marriages and perpetual misfortunes.

They had questions. But, mostly, they were just stunned.

For years, Wright Isaacs wondered why Lora Lee never responded to her outreach. “She tried so hard to find me when she was young, and my mother wouldn’t allow it. So, you know, what she’s supposed to do, you know, go away? She did.”

The revelation that Lora Lee had given up her daughter for adoption filled them with sadness and hope.

“We could find Donna Ann, you know?” Wallace softly suggested.

Wright Isaacs and her daughters are kind, gentle people. They found it difficult to understand how their own family could turn Lora Lee over to Catholic Charities.

“It’s a lot to take in and it’s very sad to think that her life could have been so different,” Wright Isaacs said. “And I guess the one thing that upset me more than anything is … she was sent to different foster homes.”

They listened politely as I discussed her marriages. Then Wright Isaacs balled up her shirt in her fists and began to cry. “He pimped her out. That’s awful. That’s just so beyond me.”

As morning turned to afternoon, Wright Isaacs pondered the precariousness of life and how much is left to fate.

“I was very well cared for. I had beautiful clothes. I had a beautiful home, a nice place to sleep, food every night on my table,” she said.

“And I’m just thinking how lucky I was,” she told me.

“Uncle Otto found her, and they used her because they were money-crazy, I think.”

Wright Isaacs recalled how loving Lora Lee was toward her when she returned to Texas. “If I had gotten ahold of her at one point in life, maybe things would have been different or maybe they’d have been worse, I don’t know,” she wondered aloud.

“She could have been anything. In my heart, I guess I always hoped that she would have married somebody wealthy, and she would have lived the life that would have been a great life,” she said.

For years, so much of Lora Lee’s life remained a mystery to Wright Isaacs and her daughters.

“I did not expect her life to be such a tragedy,” Wright Isaacs said.

And now it was time to let it go. “I’m not going to dwell anymore,” she told me. “Maybe someday we’ll meet again in heaven. I’d like to believe that, but I don’t know now.”

“I’m sorry it’s not a better story,” I told them.

A short while later, after we finished talking, I found Wright Isaacs sitting in another room. She had kept her composure for so long and was now sobbing.

The family members had waited so long to learn what had happened. Now they were having a hard time wrapping their heads around it.

Every family has secrets. I thought about the value of learning them, and the pain of it.

Then I left the family to the privacy of their own grief.

Wright Isaacs hugged me. “I got closure,” she told me. “But it’s heartbreaking.”