A biennial inhabited by centaurs, myths and homicides – We Make Money Not Art

Last month, I visited the Venice Biennial, took hundreds of photos and finally found the time to sift through them. Here are my favourite works from the massive exhibition:

Loukia Alavanou, Oedipus in Search of Colonus (still detail), 2022. The Greek Pavilion at the 59th Venice Biennale

Loukia Alavanou, Oedipus in Search of Colonus (still detail), 2022. The Greek Pavilion at the 59th Venice Biennale

Loukia Alavanou, Oedipus in Search of Colonus (still detail), 2022. The Greek Pavilion at the 59th Venice Biennale

Loukia Alavanou, Oedipus in Search of Colonus, 2022. The Greek Pavilion at the 59th Venice Biennale

Loukia Alavanou’s virtual reality 360° film and installation Oedipus in Search of Colonus links Classical Greece’s culture to the social reality of today, by showing the life of Romani families in Nea Zoi, west of Athens. Like in many other European countries, Romani communities live at the margins of city, often without access basic services such as water and electricity, and often exposed the harassment, threats and discrimination.

In Oedipus in Search of Colonus, Romani people are cast as actors for a Sophocles play and the impoverished outskirts of Athens is the setting of the play.

The work transposes in the present days Sophocles’ almost 2500-year-old drama, Oedipus at Colonus which describes the end of Oedipus’s tragic life. Sophocles set the place of the death of the mythical Greek king at Colonus, a village near Athens and also Sophocles’s own birthplace. In “Oedipus at Colonus”, the now disgraced and blind king is looking for a place that will host him and allow him to die peacefully. He arrives in Colonus but he is repeatedly asked to leave. In Alavanou’s version, the amateur actors living in an area not far from Colonus also struggle against their fate. Often lacking any form of citizenship, they are prevented by the Greek authorities from being able to choose a burial site close to their last place of residence. Talking about Oedipus, Alavanou explains in an interview, “although Creon -his brother in law and ruler of Thebes- is the one who expelled him, he later asks to take Oedipus back, only because he knows that Oedipus’ grave has the supernatural power of saving one’s city from enemies. To put it another way, he is used for political mileage, not unlike refugees today arriving in Europe from the Middle East or Africa. They are treated more like a ‘trading’ pawn between European countries than humans worth aid and support.”

Sidsel Meineche Hansen and Therese Henningsen, Maintenancer (film still), 2018

Sidsel Meineche Hansen and Therese Henningsen, Maintenancer (film still), 2018

Sidsel Meineche Hansen explores a post-human world shaped by the growing role that technology plays in our lives. The works she shows in Venice scrutinises the transformation of sex and bodies and reveals the invisible work performed in the creation of capital.

The film video Maintenancer, made in collaboration with Therese Henningsen, documents the behind the scene life in a German brothel and in particular the labour required to clean, maintain and prepare sex dolls for the next client.

You see a caretaker inserting her arm into each of the doll’s orifices to clean them after use, applying disinfectant products, adding makeup to the doll’s nipples and putting sexy underwear back onto the inanimate body.

You follow Evelyn Schwarz, dominatrix and owner of BorDoll, and her anonymous assistant, as they go about their daily routines and you listen to them as they discuss the skills and personal attributes required to work in a brothel: the cleaning of the rooms, the budgeting and administrative tasks, the preparation of drinks but also the emotional side of taking care of customers.

By the end of the video, it is clear that sex robots will not be able to fully replicate the emotional labour involved in the sex industry.

Sidsel Meineche Hansen, Daddy Mould, 2018

Sidsel Meineche Hansen, Untitled (Sex Robot) 2018. Photo: Frank Sperling

But while the dolls in the film are soft and pliable, Meineche Hansen’s sculptures are stiff. Untitled (Sex Robot) is a strong and articulated servant while Daddy Mould is an empty fibreglass mould of a silicon sex doll. Both reference human physical functionality and commodity status.

Diego Marcon, The Parents’ Room, 2021

Diego Marcon, The Parents’ Room, 2021

Diego Marcon, The Parents’ Room, 2021

Diego Marcon, The Parents’ Room (trailer), 2021

Diego Marcon, The Parents’ Room, 2021. Backstage image. Photo: Lilia Strojec

Diego Marcon’s video The Parents’ Room opens with a computer-generated blackbird singing and swooping down onto a snowy windowsill. The scene moves into a room where a man sits on the edge of an unmade bed, a woman lying beside him. The man begins a choir-backed monologue detailing how he killed his son, his daughter, his wife and how he then shot himself. The victims then enters the scene one-by-one and sing a verse of their own. None of them tells us what caused the tragedy and they all died. The film looks like stop-motion animation. In reality, live actors play all the human roles. They wear synthetic facial prostheses. Only the eyes are theirs, the rest of their face is a thick, pale mask that makes them look bruised and not quite alive anymore.

It is peaceful, unsettling and riveting.

Pilvi Takala, Close Watch, 2021. Multi-channel video installation at La Biennale di Venezia. Photo: Ugo Carmeni / Frame Contemporary Art Finland

Pilvi Takala, Close Watch, 2021. Multi-channel video installation at La Biennale di Venezia. Photo: Ugo Carmeni / Frame Contemporary Art Finland

Pilvi Takala, Close Watch (video still), 2021

Pilvi Takala worked covertly during six months as a fully qualified security guard in one of Finland’s largest shopping centres to research how power is wielded in privatised public spaces through the private security industry.

During her shifts, she witnessed scenes of open racism but also a multitude of subtle and overt strategies for controlling behaviour between guards and members of the public, but also between the guards themselves.

For ethical reasons, Takala could not film the day-to-day experience of guards and members of the public, but she used the six months immersion to record in her notebook issues of concern related to her colleagues but also her own behaviour and attitude. The videos in the exhibition were filmed during a three-day workshop in which she, her ex-colleagues and three actors re-enact and examine incidents that have occurred at work. Together with the participants, she explores power dynamics, ideas of social justice and alternative strategies for situations that can trigger or be triggered by use of excessive force, racist language and toxic behaviour.

Takala worked with the architects Studio LA to adapt the original Alvar Aalto-designed Finnish pavilion and articulate the watched/watcher dynamics across 2 rooms separated by a one-way mirror. The front part of the pavilion reveals the methods used by the artist but obscures what is going on behind. The rear space shares the post-surveillance performances and workshops, but it also allows the audience to observe the people in the front room, who are unaware that they are being watched.

Małgorzata Mirga-Tas, Re-enchanting the World, exhibition view, Polish Pavilion at the Biennale Arte 2022. Photo: Daniel Rumiancew

Małgorzata Mirga-Tas, Re-enchanting the World, exhibition view, Polish Pavilion at the Biennale Arte 2022. Photo: Daniel Rumiancew

Outside view of Re-enchanting the World exhibition, Polish Pavilion at the Venice Biennale, 2022. Photo: Daniel Rumiancew

Hall of the Months, Museo Schifanoia, Ferrara. Courtesy Musei di Arte Antica di Ferrara. Photo: Daniel Rumiancew

Malgorzata Mirga-Tas’ work at the Polish Pavilion celebrates both to her own Roma origins and the place of women in society.

“Re-enchanting the World” consist of a patchwork of glued and sewn fabrics reclaimed from women’s clothing. They recreates twelve scenes, each divided into three horizontal sections that echo the Renaissance frescoes of the “Cycle of the Months” in the Palazzo Schifanoia in Ferrara, Italy. This cycle of the months of Ferrara connects Greek mythology and astrology with scenes of agriculture and everyday life at the court of the Duke of Ferrara. Mirga-Tas’ own version subverts traditional (and decidedly prejudiced) depictions of the arrival of the communities in Europe to regain control over the Romani visual narrative and identity.

The upper section of Mirga-Tas work charts the journeys of Romani communities across Europe. The central section represents the history of Romania from a female perspective. The third, lower section shows scenes from the artist’s contemporary daily life in Polish places close to her heart.

The title is inspired by Silvia Federici’s book, Re-enchanting the World: Feminism and the Politics of the Commons.

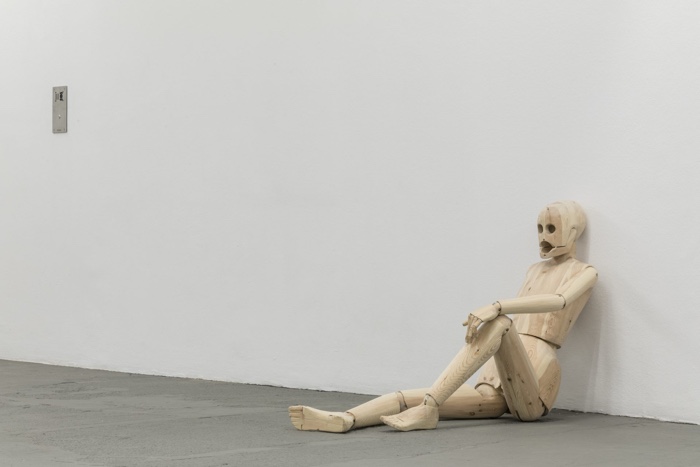

Uffe Isolotto, We Walked the Earth, 2022. The Danish Pavilion, Biennale Arte 2022. Photo: Ugo Carmeni

Uffe Isolotto, We Walked the Earth, 2022. The Danish Pavilion, Biennale Arte 2022. Photo: Ugo Carmeni

Uffe Isolotto, We Walked the Earth, 2022. The Danish Pavilion, Biennale Arte 2022. Photo: Ugo Carmeni

Uffe Isolotto talking about “We Walked the Earth”

Uffe Isolotto, We Walked the Earth, 2022. The Danish Pavilion, Biennale Arte 2022. Photo: Ugo Carmeni

Uffe Isolotto, We Walked the Earth, 2022. The Danish Pavilion, Biennale Arte 2022. Photo: Ugo Carmeni

Uffe Isolotto, We Walked the Earth, 2022

No one knows the circumstances that lead to the drama unfolding inside the Danish Pavilion. A centaur just hung himself. He is in the line of sight of his female companion. Laying on the floor in another room, she is giving birth.

The scenes are hyperrealistic. The house is derelict, like a farm that has seen better days. You walk around the rooms like a voyeur, looking at its enigmatic inhabitants, their meagre belongings and working tools. You try to reconstruct their story but the exercise is futile. Are these creatures future humans who have evolved to survive in radically changing world? Are you just observing a scene from the life of mythical creatures from the books you were reading as a child?

Jacob Lillemose, the curator of the exhibition, says, ”We Walked the Earth addresses an experience of being human in a time when human life is becoming more and more integrated into – if not inseparable – from contexts and processes that are both other-than-human and larger-than-human. Does that mean that we need to expand the notion of what it means to be human? That’s the fundamental question the installation asks.”

Jessie Homer French, Oil Platform Fire, 2019

Jessie Homer French brings the American wildlife and pastoral life into a contemporary atmosphere characterised by pollution, wildfires, extractivism, wind farms and other violent forms of human encroachment. The artist has been painting these scenes of challenges to the survival of the planet since the 60s, long before these themes were seen as imperative as they are today.

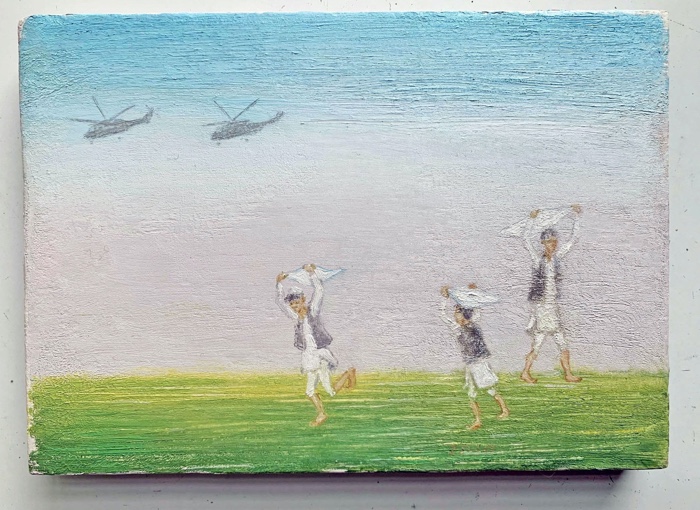

Francis Alÿs, Untitled, Bamiyan, Afghanistan, 2010

Francis Alÿs, Untitled, Ciudad Juarez, Mexico, 2013,

For the exhibition in the Belgian Pavilion, Francis Alÿs presents a selection of short films shot since 2017 in Hong Kong, Democratic Republic of Congo, Belgium, Mexico, etc. What got my attention, however, was the series of small paintings covering a period from 1994 to 2021 that provide the context in which some of the films were made. From Kabul to Ciudad Juárez, from Jerusalem to Shanghai, children are seen creating joy and entertainment whatever the conflict situation and surrounding they find themselves in.

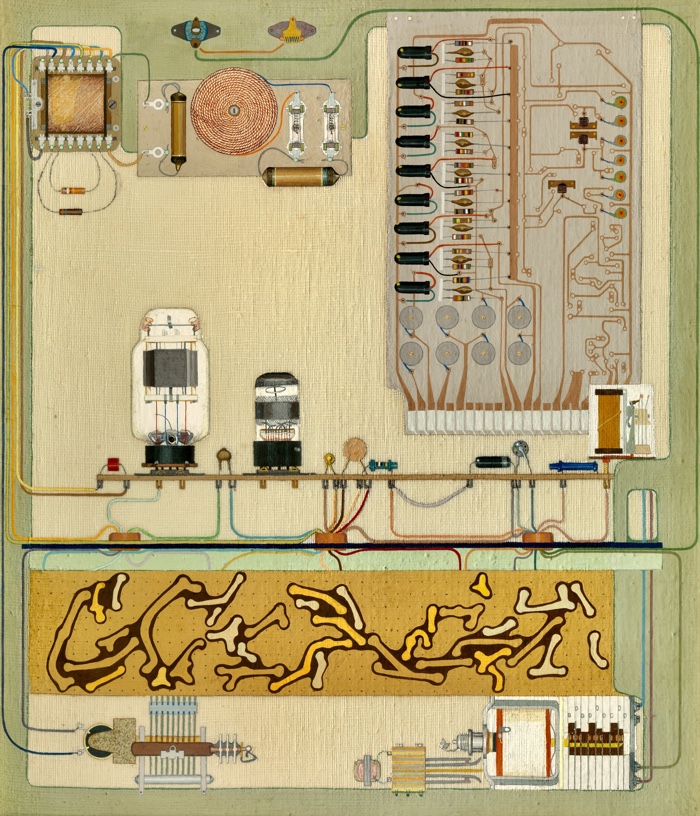

Ulla Wiggen, Kretsfamilj (Circuit Family), 1964. Photo: Åsa Lundén/Moderna museet

One of the best surprises of the show for me was a series of acrylic and gouache paintings on wood panels portraying the interior circuity of electronic devices. They were made by Ulla Wiggen who, when she was twenty-six years old, took part in the 1968 exhibition Cybernetic Serendipity curated by Jasia Reichardt at the ICA London.

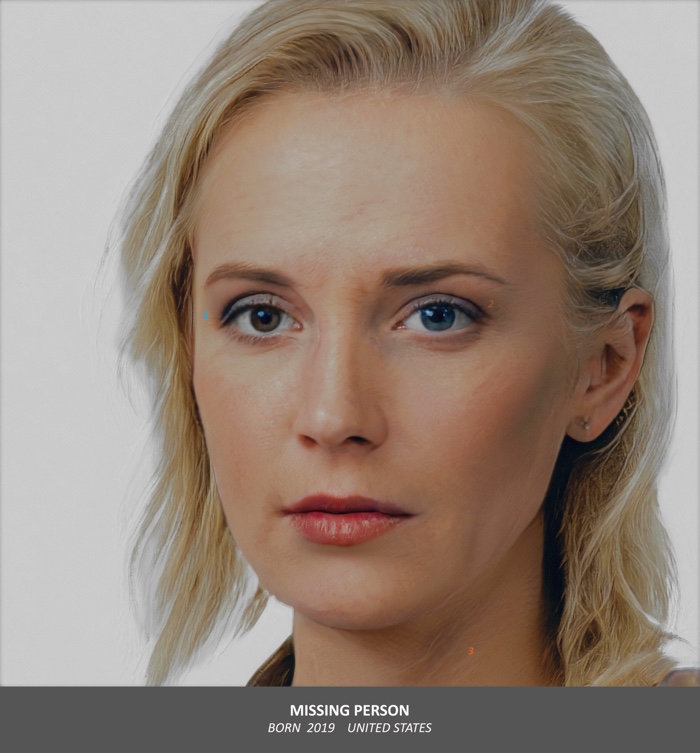

Lynn Hershman Leeson, Missing Person Born 2019, 2021

Miriam Cahn, Part of “Unser süden sommer 2022”, 5.8.2021, 2021

Paula Rego, Gluttony, 2019. From the series Seven Deadly Sins. Photo: Riccardo Bianchini / Inexhibit

Also at the Venice Biennial: Orchidelirium. Colonialism through the lens of botany.